Molecule of the Month: Enoyl-CoA Carboxylases/Reductases

Enzymes that can quickly and efficiently fix carbon

A more efficient way of fixing carbon

Enzymatic Synchronization

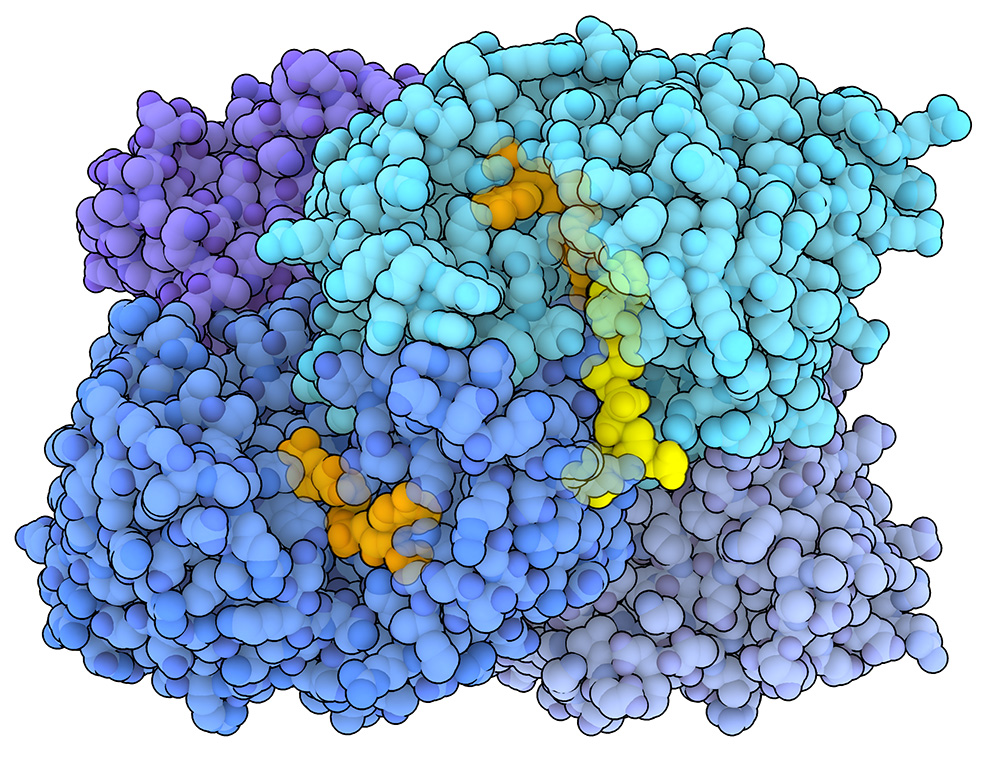

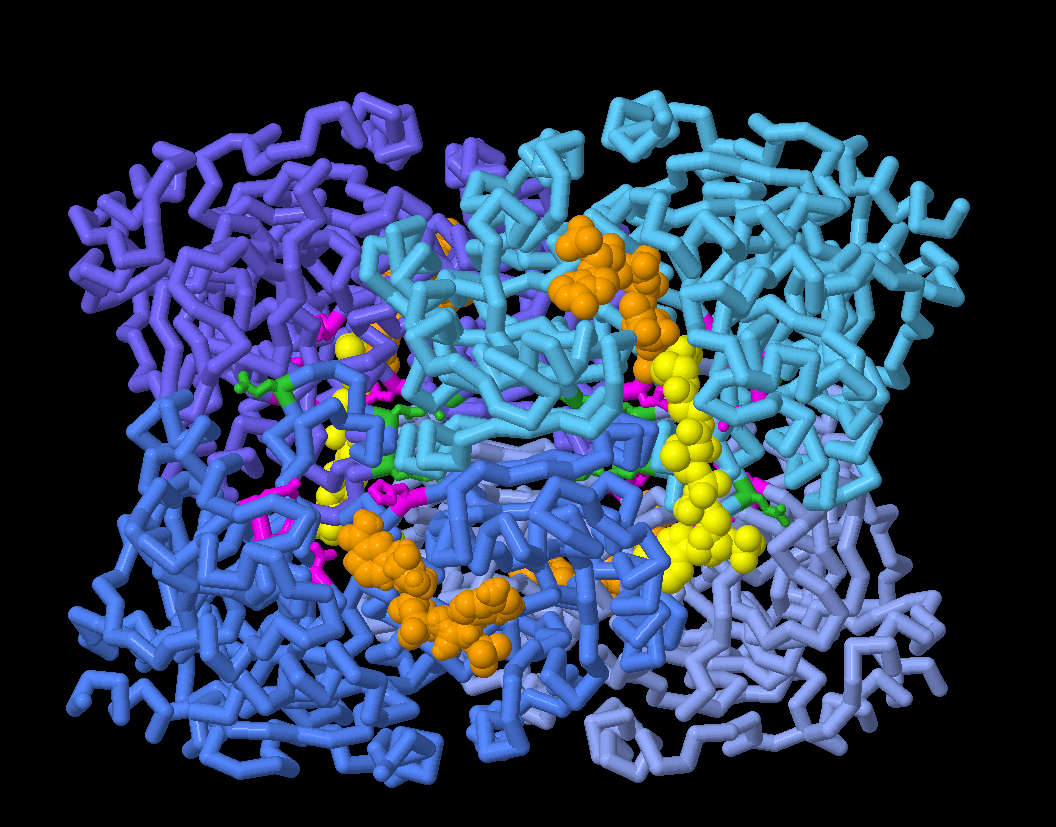

Exploring the Structure

Taking a closer look at carbon fixation

In the JSmol tab, you can explore the structures of different ECR conformations and take a closer look at amino acid residues thought to be involved in binding carbon dioxide (shown in magenta), plus residues involved in coordinating enzymatic synchronization (shown in green).

Topics for Further Discussion

- Rubisco, considered to be one of the most abundant enzymes on the planet, is used by plants and algae to fix carbon dioxide.

- Cyanobacteria also use Rubisco, storing multiple copies of the enzyme in an organelle called the carboxysome. Read more about this and other carbon capture mechanisms

- This study took advantage of time-resolved crystallography techniques, which have also been used to study other enzymes that rapidly catalyze reactions, including studies of light activatable proteins.

Related PDB-101 Resources

References

- 6OWE: Stoffel GMM, Saez DA, DeMirci H, Vögeli B, Rao Y, Zarzycki J, Yoshikuni Y, Wakatsuki S, Vöhringer-Martinez E, Erb TJ. (2019) Four amino acids define the CO2 binding pocket of enoyl-CoA carboxylases/reductases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Jul 9;116(28):13964-13969.

- 6NA3, 6NA4, 6NA5, 6NA6: DeMirci H, Rao Y, Stoffel GM, Vögeli B, Schell K, Gomez A, Batyuk A, Gati C, Sierra RG, Hunter MS, Dao EH, Ciftci HI, Hayes B, Poitevin F, Li PN, Kaur M, Tono K, Saez DA, Deutsch S, Yoshikuni Y, Grubmüller H, Erb TJ, Vöhringer-Martinez E, Wakatsuki S. (2022) Intersubunit Coupling Enables Fast CO2-Fixation by Reductive Carboxylases. ACS Cent Sci. 2022 Aug 24;8(8):1091-1101.

- Schwander T, Schada von Borzyskowski L, Burgener S, Cortina NS, Erb TJ.(2016) A synthetic pathway for the fixation of carbon dioxide in vitro. Science. Nov 18;354(6314):900-904.

March 2025, Janet Iwasa

http://doi.org/10.2210/rcsb_pdb/mom_2025_3